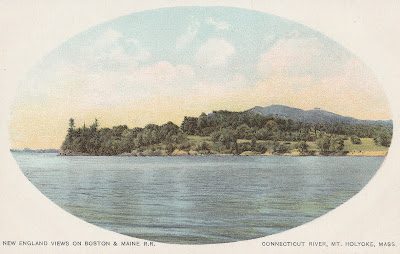

Quabbin Reservoir from the Prescott Peninsula, 1991, photo by J.T. Lynch

This coming Saturday, April 27

th, a celebration,

a commemoration, and a reenactment of sorts of the final Farewell Ball of the towns

demolished to make way for the Quabbin Reservoir will be held in Ware,

Massachusetts. (For more information, see this

Friends of Quabbin, Inc. site.)

The dismantling of four entire towns in the 1930s—Prescott,

Enfield, Dana, and Greenwich—to construct the Quabbin Reservoir in Central

Massachusetts is a remarkable feat of engineering, a sorrowful exodus, and a

compelling historical event that surfaces from time to time in

anniversaries.

The last generation of

children growing up during this strange era have mostly left us, and so the

archival resources of the Friends of Quabbin in Ware and the

Swift River ValleyHistorical Society in North New Salem are ever more important.

Many years ago, I was privileged to research and write about

these events for a western Massachusetts monthly historical magazine, called Chickuppy & Friends. One of that last generation I interviewed was

a lovely lady named Eleanor Griswold Schmidt.

She gave many interviews to local press, and was eager to talk about the

experiences of the Swift River Valley residents forced to give up their

homes. I sensed she felt that passing

the story along was duty she paid to her parents and their former town of

Prescott, to not let it be forgotten.

Mrs. Schmidt is no longer with us, except in her words. What follows is the article that resulted

from one of our talks together, originally published in May 1986. She paints a picture of a town and a

lifestyle in the details of everyday life.

****

Prescott was a farming community. There were a few stores and a couple

churches, but mostly it was farm after farm with miles between neighbors. Eleanor Griswold Schmidt and her five

brothers and sisters grew up on their Prescott farm in the 1920s when Prescott

was “folded up and no longer a town.”

The town met its official demise in 1938, but due to the weight of that

forced change, most of the population evacuated during the 1920s. The Metropolitan District Water Supply

Commission (MDWSC), which managed the Quabbin Reservoir project, helped to

support a town government in Prescott in 1926 just to keep the town offices

officially open until the town's scheduled demise on April 27, 1938.

The children of remaining families, like the Griswolds,

lived through the change in their community and observed the death of their

town. The “death” was the loss of its

people.

Her parents, Mr. and Mrs. Griswold, came to Prescott as teenagers

in the late 1800s. Mr. Griswold’s family

was from Huntington. Mrs. Griswold’s

family, the Smiths, came from their old farm around the present-day site of

Bondi’s Island in Agawam, Massachusetts.

Algie Griswold and Olive Smith married in 1911, and all their six

children were delivered by one of the more well-known men in the Swift River

Valley, Dr. Willard Segur, in Mary Lane Hospital in Ware.

Eleanor was the eldest, followed by Eddie, Lyman, Doris,

Beatrice, and Frances, the last born in 1924.

The Griswolds’ entire living was made from the farm, from the milk of

their dairy cows, which they brought to the train in Enfield, to be taken to

Springfield. Their refrigeration was

from the ice harvested from the local ponds in winter. The boys and girls in the family had chores

divided among them, and helped out in every part of running the farm. While the boys were busy in the barn, there

was housework for the sisters, and the tending of the ducks, pigs, and

chickens. They brought eggs to the A.H.

Phillips store in Enfield to turn them in for groceries.

The store and post office in Prescott had gone by the late

twenties. There were fewer telephones by

the late twenties, and there had never been any electricity or running water

where the Griswolds lived. But they

lived self-sufficiently as farm families can, wanting little, needing less.

According to Eleanor Griswold Schmidt, “The surplus from a

family of eight was what the public got a chance to buy.” Haskell’s store in Enfield had clothing and

notions. They bought from the Charles

Williams store catalogue and the Montgomery Ward catalogue for clothing.

There were Katzenjammer Kids funnies

plastered on the insides of the outhouse.

Hans und Fritz had truly been everywhere.

They made cakes and pies, ice cream to sell from a stand in

front of a church at the four corners.

On summer weekends, people came from all directions: Enfield, Pelham,

and Greenwich, and bought homemade ice cream for a nickel from the Griswold

kids: chocolate, vanilla, strawberry (if they were in season).

Most days, breakfast was home fries, eggs, bread and

butter. Mrs. Griswold made a kind of

coffee drink for the kids ground out of bread crusts that were browned in the oven. There was hot cereal in the wintertime for

the two-mile walk to school. The kids

got up at six o’clock, did the milking, fed the cows, chickens, all the

animals. The cows were driven down to

water. The barn was a warm place, even

in the winter, from the hay stored and the body heat of the animals. The brothers and sisters came back to the

breakfast table to eat in shifts whenever they were done. There was strong-smelling Fels-Naptha soap

bar with its mottled orange wrapper for the dishes. A pump at the sink, the water was heated on the

stove.

“It’s such a good thing today, electricity,” said Mrs.

Schmidt. The whites were boiled on the stove

as well in a copper kettle. Clothes were

also washed in a mechanical washing machine with a handle to turn. “A hundred and twenty times, and then you can

play.” This was done outside.

The clothes were put through the wringer and hung, the whole

sunny yard filled with flapping laundry.

School started at nine a.m.

The Griswold children were taught by Miss Marion Kelly at Prescott

School No. 3, a one-room schoolhouse.

The children of each grade were taught together at the primary

level. After that, it was high school in

Belchertown. There were under thirty

children in the school at the time the Griswold children attended, two or three

to a grade, as it happened, and Miss Kelly managed them all. It was a system that encouraged and relied

upon the children’s independence.

“You had your work to do.

If you didn’t get it done, there was nobody but to blame but yourself,” Mrs.

Schmidt said.

The kids respected and liked Miss Kelly, and there was no

nonsense, and also no books to take home.

All practice work was done at school.

With chickens and cows, there was already too much to do at home. It was in the schoolroom that they practiced

their precise Palmer handwriting and memorized multiplication tables, backwards

and forwards, and backwards again.

“I think the little ones were the ones who made out the

best, because they could hear everything that was going on, so they could come

along a little bit faster,” said Mrs. Schmidt.

“You had to kind of learn on your own, I guess. Nobody ever sat beside you or helped you in

any way.”

Prescott Hill No. 3, date unknown, photographer unknown. Image Museum website.

A visiting music teacher came at intervals as well. Report card results were their own

reward. Sometimes. Mrs. Barbara Fuller and her husband, Clarence,

ran the store and post office in that part of Prescott, and she promised

chocolate drops to the kids if they got an “A” in music. Mrs. Fuller also gave piano lessons. Mrs. Schmidt remembers the time she missed

getting an “A”, and Mrs. Fuller said, “’What’s wrong with the spelling,

Eleanor? You can do better than that. Get an “A” in spelling and...’ She didn’t

discriminate,” Mrs. Schmidt said, “She knew I wasn’t trying and this was her way

of snagging me, and it worked.” She took

piano lessons from Mrs. Fuller herself and found a great friend in her. “She had a box of jewelry that was her mother’s,

and she let me put them on, and then she gave me a very pretty thing of her

own. It was a locket with her picture on

it.”

The Fullers closed their store and post office, and joined

the exodus in 1928.

Lunch at school was a covered dinner pail with jelly

sandwiches, or cheese, or peanut butter.

Across the road from the school was a well and a tin dipper. Children brought a cup from home, or just all

drank from the same dipper. Besides the

half-hour recess, there was a short break in the morning and afternoon, enough

time for an apple for a snack.

There were two entrances at the school: one for the boys and

one for the girls, just as there were two separate outhouses for the boys and

girls. Classes may have been more or

less informal in a one-room school, but rules and customs were strictly

observed.

“She was a lovely person,” Mrs. Schmidt said of their

teacher, Miss Kelly. “There were no

lickings. I never saw any kid get

hit. My brother had to go to the

entryway once (where punishments were administered), and I never knew what

happened to him, but you’re mortified knowing your brother’s out there. He said he didn’t do it, and he told me

himself only a few years ago, he said, ‘You know what really happened? She whacked with a pointer a coat so it made

a whack, whack, whack noise, and Miss Kelly

said, ‘I wan’cha to holler a bit, too.’

She never did anything to him, but everybody thought, ‘Oh, is she

murdering him!’”

Miss Marion Kelly left too, and according to Mrs. Schmidt was later a teacher in

Wilbraham, eventually to become a principal there. She is remembered by her former students as

well as for the Christmases she gave them.

The kids received candy, an orange, a pencil box and pencils with the

child’s name on them, a calendar with a picture of that child’s grade

classmates on it. Even a classroom

tree. It was, “a Christmas that a lot of

the kids didn’t have at home.” It all

came out of her own pocket and her heart.

Like the children, she walked to school herself on the empty, dusty

roads in Prescott.

The student body, teacher, and visiting canine friend of Prescott Hill School No. 3. Date unknown, but probably long before the Griswold kids attended. Image Museum website.

Besides Miss Kelly and the visiting music/singing teacher,

the superintendent of schools visited, perhaps twice a year, and the children

had to be on their best behavior.

“He was the President of the United States as far as we were

concerned,” Mrs. Schmidt said of the strange, austere figure. “Somehow, you felt scared to be in his presence.”

Her church, the Prescott Congregational, also served as a

schoolhouse. This building, too, joined

the exodus and now stands as the Skinner Museum in South Hadley. There were Sunday School activities as well,

bibles won for scripture memorized, and plays.

The children came home to bread and vegetables for supper,

perhaps a dessert called junket, a kind of custard made of sweet milk. Sunday dinner was the big meal of the week,

with corned beef, dried beef or codfish.

Their chickens were for laying eggs, not for eating, although one may

have found its way into a soup from time to time, or for Thanksgiving and

Christmas.

They would often take Sunday dinner at their Grandmother

Griswold’s after church. They also went

there for Christmas. A hemlock tree was

there, strung with popcorn and cranberries, but no candles. Prescott was rural, with no fire department,

so candles were too dangerous on a tree.

There were dolls for the girls one year, and under their Christmas tree,

simple toys, and perhaps a hat or boots, or leggings for the winter walk to

school, or mittens cut out from an old coat.

The Griswold children hung their stockings. Depression Christmases. If they found coal in their stockings, it

wasn’t because Santa Claus was mad at them; it was because their parents had

nothing else. “That was just a symbol to

us that our parents were sorry,” said Mrs. Schmidt. “Those were times that there were tears that

we never saw, but we knew.”

Other than the occasional Grange doings, there were no town

gatherings in the dwindling town, not beyond the Memorial Day ceremony at the

cemetery where children from the schools read their poems. There were family celebrations, though. Uncles who shot off fireworks on the Fourth

of July.

The Griswold children played around the ponds, fished,

hunted for lady’s slippers in the summer woods.

Some of their neighbors left.

Other farms were occupied by renters in the summer who rented land back

from the MDWSC, which had purchased it from the owners. But there were six Griswold kids and they

didn’t need to walk to a neighbor’s home miles away only to have to return for

supper. They had themselves, their parents,

their farm. The older ones looked after

the younger.

“There was a lot of responsibility, a lot, and I’m glad, because

you knew all your life you were responsible for others as well as yourself.”

About 1930, Mr. Griswold bought a Model T Ford and

terrorized his children with his lack of driving skills. “We kids never liked to ride with him because

he never knew how to drive. He was all

right with horses, but couldn’t do much of anything with a Model T,” Mrs.

Schmidt said.

Later in her teens, Eleanor left home to work in a Greenwich

store and board with a family there. She

earned $7 a week at SR King’s store, plus room and board. It was general store that sold everything

from meat to boots, and dry goods, cookies in bulk, National Biscuit’s, “Raspberry

Ripples.” Many customers bought on

credit in these Depression days. Many

had already moved out of Greenwich and left the Valley for good.

The main populace there at the time were the “woodpeckers,”

the men who were brought in to cut trees and clear brush, the men who were

building Quabbin Reservoir.

“I loved it because all the woodpeckers and workers were

there,” said Mrs. Schmidt, whose nickname among them was “Peaches,” one of the

few single girls for miles. Most of the

men were married, but they joked with her and flirted, and Mrs. Schmidt said it

wasn’t a bad place to be when you’re the only single girl for miles.

After 1937, she went to work for another store in North

Amherst, $10 a week, six days a week.

There was an ice cream and soda bar there, and a lunch counter where she

made sandwich lunches for the teachers.

Back at the Griswold farm in Prescott, the last of their neighbors left

in 1933. There was no store telephone after ’33. Her family was isolated in Prescott, and felt

the brunt of that isolation during the Hurricane of 1938. Eleanor’s fiancé, Edward Schmidt, walked ten

miles through debris to reach the Griswold farm and back to Eleanor in North

Amherst to report on their safety.

Mr. Griswold had died in 1937 of a ruptured appendix. Dr. Segur couldn’t help. To the end, Mr. Griswold never wanted his

land to be sold. Ultimately, he didn’t

have to witness it when his family sold and moved to Amherst.

Eleanor became Mrs. Edward Schmidt in 1939.

“Mine is a slanted, different childhood,” Mrs. Schmidt said

of the experience growing up in a dying town that they knew, even as young

children, was dying. There was a struggle

against it in Prescott as there were in the other towns, but it was also a

nation in Depression. They were going to

lose their homes. No matter what they did,

they were going to lose their homes.

Much of Prescott was not inundated by the reservoir, and

instead, became a wildlife sanctuary. On

the old Griswold farm, an open hayfield is now wooded. Mrs. Schmidt has obtained permission a few

times to return to the spot.

“Nothing is familiar,” she said. The farming community has returned to the wilderness.

The Prescott Peninsula, 1991, photo by J. T. Lynch

***

My novel,

Beside theStill Waters, is a fictional account of the people in the “Quabbin towns.”

I’ll be posting more about that in weeks to

come in this, the 75

th anniversary of the disincorporation of Dana,

Enfield, Greenwich, and Prescott, Massachusetts in April, 1938.