This view of a sailboat is off Falmouth, Mass., looking across the water towards Martha’s Vineyard. A reminder of our memories of summers past, and a reminder that this last winter is now past, too, even if it doesn’t feel like it, yet. Better days are coming.

Tuesday, March 31, 2009

Sailboat off Falmouth, Mass.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:27 AM

4

comments

![]()

Labels: Massachusetts, seascapes

Friday, March 27, 2009

Candlepin Bowling

The three objects above are identifiable probably only to New Englanders. They are, of course, candlepin bowling balls. The sport created in New England is played only here and in some of the Canadian Maritimes.

The sport actually is less popular in Rhode Island and Connecticut, but I’d love to hear from our friends in these states to know if they’ve been candlepin bowling in their communities, or if it’s duckpin they prefer. Or ten-pin, which some New Englanders call “big balls.”

We have Justin White to thank for this sport, who in 1879 bought a billiard and bowling business in Worcester, and developed the game. Bowling of one form or another had been around since people lived in caves, but Mr. White made some refinements, and this particular game’s popularity took off.

For our friends not familiar with candlepin bowling, the game is a bit harder than ten-pin bowling (big balls). The pins are more narrow and streamlined (like candles), the balls are smaller (like grapefruit). The balls can frequently pass right through the spaces between the pins and hit nothing, prompting much harassment from fellow bowlers.

Ten-pin? Heaving a giant ball at a bunch of fat pins, of course you’re going to knock something down. Big deal.

Each game in candlepin is called a string, and a bowler gets three tries each box to knock ‘em down. We leave pins up in configurations called “the four horsemen” or “spread eagle” or a “half Worcester”.

Many of us grew up watching Don Gillis on “Candlepin Bowling” on TV. For more on candlepin bowling, have a look at this website.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:34 AM

11

comments

![]()

Labels: 19th century, 20th Century, New England, sports

Tuesday, March 24, 2009

Hartford - Insurance Capitol

A children’s coloring book from years ago taught about the 50 US state capitols. Each page in the coloring book featured an iconic image to color about each state capitol. I think Boston’s picture was of a Pilgrim, or possibly a Minuteman. State capitols from the Midwest featured ears of corn or Abraham Lincoln, or the St. Louis Arch. There were images of Alaska and Kansas, Florida orange groves, of fishing boats, the Liberty Bell, oil rigs, cowboys, and lobstermen.

The page for Hartford, Connecticut had a picture of an insurance policy.

Once called the insurance capitol of the world, Hartford continues to host many insurance company headquarters, and it is still a major industry here.

Here we have Travelers, Aetna, CIGNA, Phoenix Mutual, and of course, The Hartford. Some companies, like MetLife and MassMutual have moved out to the suburbs. Those that remain occupy buildings that are bastions, famous for their architure.

Aetna’s headquarters is considered the world’s largest colonial revial-style building. Above we have a shot of the distinctive Traveler’s building. Contrasting these traditional architectural forms, is the Phoenix Mutual Life Insurance Building, a modern structure reputed to be the first two-sided building in the world, and as such, is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Aetna issued its first life insurance policy in 1850. According to the website of The Hartford, among its most famous customers was Robert E. Lee, who in 1859 took insurance out on his home, which as General of the Army of Northern Virginia during the American Civil War, he lost when the Union Army began to bury its dead in his front yard. His home is now Arlington National Cemetery. One wonders if he was insured for Civil War.

President Abraham Lincoln also took insurance with The Hartford out on his home back in Springfield, Illinois in 1861, which he would never see again, after his Presidendency ended with his assanation.

In 1890 Buffalo Bill Cody collected on a claim after a fire on his property. In 1920, the same day Babe Ruth was traded by the Red Sox to the Yankees, Ruth bought a “sickness” policy to protect his income should illness threaten his career. The Red Sox should have bought a Curse of the Bambino Policy the same day.

In 1947, the Junior Fire Marshal Program began, and many of us were taught in school the basics of fire prevention, and took home one of these little toy badges. Check out eBay sometime and you’ll see many of them still exist.

Perhaps some of you fans of Old Time Radio will remember “Johnny Dollar” an insurance investigator working out of a fictional Hartford-based insurance company.

Next year The Hartford will celebrate its 200th anniversary. There is more to Hartford than the insurance industry, but page in a coloring book devoted to an insurance policy must tell us it’s at least as important as a cowboy or a Minuteman. Probably not as much fun to color, though.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:25 AM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: 19th century, 20th Century, business, Connecticut, Presidents, sports

Friday, March 20, 2009

Frog Bridge - Willimantic, Connecticut

If you’re ever driving alongside the Willimantic River and you happen to notice a large frog sitting on the top of what looks like a spool of thread, or a couple of them, you’re either very tired or you’ve arrived at Frog Bridge.

Willimantic, Connecticut used to be known as Thread City because the American Thread Company had a mill here and it was once one of the largest producers of thread in the world.

The frogs are for something else entirely. They don’t have anything to do with the thread.

An event during the French and Indian War, back in 1754, is the purpose for those big frog sculptures. Hearing a frightening cacophony of heaven knows what one night, the villagers grabbed their flintlocks expecting to fend off an Indian Attack.

There was nothing. Nothing but the wild noises from a wilderness.

The next morning they discovered the horrific noise was caused by hundreds upon hundreds of frogs who were battling over water in a nearby dried up pond. The survivors of this Battle of Frog Pond as it came to be known, hipity-hopped down to the Willimantic River, and one presumes, with much relief to all, frogs and people.

In the late 1990s when it was time for a new bridge, these sculptures of frog and thread were plunked as proud symbols of Willimantic’s history, and maybe Willimantic’s sense of humor. Their ancestors might have been frightened out of their beds by the froggy battle, but their descendents got a new four-lane bridge, and the last laugh.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

8:01 AM

8

comments

![]()

Labels: 18th Century, 20th Century, Connecticut, tourism

Tuesday, March 17, 2009

Colonial St. Patrick's Day

Though St. Patrick’s Day has become identified with Irish nationalism and Roman Catholic observance of a saint’s day, this holiday’s origins in America were Protestant and British.

It began in Boston in 1737, and for the rest of the story, allow me to refer you to my article posted at Suite101.com on the colonial St. Patrick’s Day.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:18 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: 18th Century, colonial period, holidays

Friday, March 13, 2009

The Blizzard of 1888

The above photo (in public domain), is of Grand Street in New Britain, Connecticut in the aftermath of the Blizzard of 1888. During the blizzard, one of the worst nor’easters to ever affect New England, a person couldn’t see the hand in front of his face. Many died walking only feet away from shelter, becoming disoriented in the storm. It was called The Great White Hurricane.

The photo was a stereopticon picture published by F. W. Allderige of New Britain. It is not the only lasting souvenir. Shocked by how Boston was incapacitated by the storm, as were so many other cities, plans were set into motion to create that city’s, and this nation’s first, subway.

The storm barreled up through New Jersey and New York, its origins on March 11th, and the worst of it would last some three days. Many people were trapped in their homes, or at work, or on the train for a solid week. People burned whatever they could to keep warm, and ate whatever they could find. Four hundred people died, at least half that in New York. About four feet of snow fell in New England, and the drifts were measured up to 40 feet high. Winds of 54mph were reported at Block Island.

The rural parts of New England fared a bit better than the cities, where people on farms were more apt to make do on what they put by. City people reliant on infrastrure, as well as on jobs in stores and factories, went hungry quickly when their work places closed. Food supplies ran low in Springfield, Boston, Worcester. Most people heated their homes with coal, and that ran low, too. Trains were stuck, and couldn’t bring in more.

When it was time to dig out and clean up, the snow was dug out by hand and hauled away on horse-drawn sledges. Slow work.

It was a deceptive storm from the first, as the days preceding it were springlike and warm with spring officially a little over a week away. When the storm did arrive, it came first in the form of rain. Then the bottom fell out of the thermometer, and Mother Nature let us know again, and she does often, that spring happens when she says so and not when the calendar does.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:28 AM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: 19th century, Blizzard of 1888, New England

Tuesday, March 10, 2009

G. Fox & Co. - Hartford, Connecticut

Above is something we don’t see too often anymore, a hatbox. It is from a store we no longer have here in New England, Hartford’s grand and famous G. Fox & Company.

G. Fox holds a special place in the memory of its employees and especially its thousands upon thousands of customers. It was unique among many grand department stores which stood as flagships for thriving cities in that it never did branch out into the suburbs, not when it was operated by the Fox family. There were never any outlet or branch stores of G. Fox, just the one. It was among the first in New England to adopt progressive policies for the treatment of its employees, and was among the first to hire African-Americans in administrative positions.

It was also run by a single family, and during its golden period from the late 1930s to the mid-1960s, by a single remarkable woman.

Beatrice Fox Auerbach was the third generation of the Fox family to run the store. It had been founded by her grandfather Gershon Fox as a dry goods store in 1847 as I & G Fox. Hartford was a burgeoning city in the late 1800s. It more than thrived; it catapulted itself into one of the most prosperous and commercially energetic cities in the country.

G. Fox went from father to son, and then for a time, granddaughter Beatrice along with her husband George Auerbach joined the business. When Mr. Auerbach died in 1927, Beatrice ran the store equally with her father, Moses Fox. The store was now an 11-story Main Street building put up after a fire destroyed the prior building in 1917.

When her father died in 1938, Beatrice took the helm alone, and was responsible for guiding the business to its golden age. There were many expansions, renovations to the building, the adding of air conditioning, the application of Mrs. Auerbach’s elegant taste to the décor, and the addition of host of services to the customer including phone orders and home delivery.

Many recall eating at the luncheonette in the store, or the more grand tea room called The Connecticut Room with its murals of 19th century Connecticut. Her own farm in Bloomfield supplied produce and dairy products.

What Mrs. Auerbach displayed in her approach to her running of G. Fox was more than a willingness to reinvest in her business, but also an eagerness to invest in her community. Her interest in Hartford and her staunch support of the community was famous.

G. Fox was sold to the May Company in the late 1960s, and then closed in 1992. Its like may not be seen again.

A recent comment on the post from last year about Springfield’s Forbes and Wallace (see here) added a wonderful personal insight to the description of that store. I hope anyone who remembers working, or shopping, at G. Fox (lots of folks took the train north from the Connecticut shore and south from the Springfield, Mass. area just to shop at the store) will stop by with your memories. Memories are all we have now of G. Fox. We might as well dig them out and dust them off.

For more on G. Fox, have a look at this Connecticut Historical Society website.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:27 AM

8

comments

![]()

Labels: 20th Century, business, Connecticut

Friday, March 6, 2009

Lydia Pinkham Memorial Clinic - Salem, Mass.

Above is the Lydia E. Pinkham Memorial Clinic of Salem, Mass. It was founded in 1922 by Aroline Chase Pinkham Gove, the daughter of Lydia Pinkham, once a household name in 19th century America.

Lydia Estes Pinkham was a reformer, an inventor, and an entrepreneur who combined all these three qualities into her career of marketing an herbal tonic to relieve menstrual and menopausal discomfort. Her product was enormously popular in an age when relief for painful menstruation usually meant surgery, which in that era nearly half the time resulted in death. No one wonder women of that time preferred a less risky option. Lydia Pinkham’s name and product became iconic, and sometimes the subject of bawdy humor in a more chauvinistic era.

Born to a Quaker family in Lynn, Lydia Estes and her family were strongly anti-slavery, who counted William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass among their friends. Lydia married Isaac Pinkham in 1843. Their children would all be one day involved in the family patent medicine business, which reportedly began when Lydia, as was common in the day, brewed home remedies.

Her particular home remedy for “female complaints” made a hit with her female neighbors, and was launched in production for sale to the public in 1876, now called Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compund, one of the most famous products of the 19th century. The clinic for which she is named still provides health services for young mothers and their children.

Have a look here for more information on Lydia Pinkham’s patent medicine.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:50 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: 19th century, business, Massachusetts

Tuesday, March 3, 2009

The Ames Manufacturing Company - Civil War and the New England Mill Town

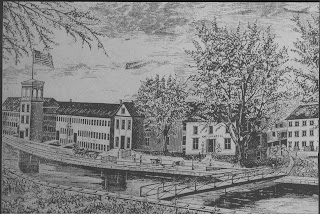

(Chicopee 1856 - Chicopee Public Library)

The following is an abridged version of an article which originally appeared in North and South magazine, June 2006.

The American Civil War came to Chicopee, Massachusetts not as a battlefield, but in the form of textile mills, an arms manufacturer, and over 700 military volunteers. This community illustrated Northern Civil War experience in microcosm.

Chicopee’s most prominent family, called Ames, profited by the war, and was struck down by financial hardship as well as personal tragedy at the war’s end.

Ironically, while the Ames Manufacturing Company produced weaponry for a war to put down Southern rebellion and would bring an end to slavery, across the street and sharing the same canal for water power was a cotton textile mill that thrived on the existence of slavery to grow and harvest the cotton cheaply. It was town, and a time, full of paradox.

Correspondence which crossed the desk of James T. Ames, the factory’s owner, included this typical letter from Alfred Barbour, Superintendent of the Harper’s Ferry Armory, dated December 17, 1860.

“Dear Sir;

You will please furnish for the Harper’s Ferry Armory one hundred

and twenty tons of Marshal iron in molds or shapes suitable for

rolling into barrels; as you have heretofore furnished. The price will

be two hundred dollars per ton….” (1)

Soon, there would be no more orders from the South with the coming hostilities, and the U.S. Government due to the loss of Southern arsenals would come to depend more upon the independent manufacturer. (2) By 1864, the Ames Manufacturing Company would be the among the Union’s most important private manufacturers of side arms, swords, and light artillery, and the third largest producer of heavy ordnance. (3)

The coming war would create a maelstrom of contradiction for James T. Ames. He was already a prominent man in Chicopee, and representing an industry which was now of top importance to the United States government once the Southern states seceded, but he also turned a profit selling to the soon-to-be enemy before the embargo on such sales was enforced. As the above letter illustrates, Ames swords were purchased by the states of Virginia, Mississippi, Maryland, and Georgia as late as 1860. (4) War, by this time and to most people, seemed unavoidable, and these customers would soon be the enemy.

For James T. Ames, the coming war meant another personal conflict, with his friend James H. Burton of the Richmond Armory, a man whom he had helped to obtain the position of Master Armorer at Richmond. By June 1861, Burton had been appointed Lieutenant Colonel of Ordnance of Virginia, and in December, he was appointed Superintendent of Armories of the Confederate States of America. (5)

Another contradiction was that Ames’ factory would produce the most modern ordnance then known, yet such weaponry would tear to pieces men still incongruously brandishing as weapons James T. Ames’ most renown product, the Ames sword.

(Ames Mfg. Co., 1860s - Edward Bellamy Memorial Association, Chicopee, MA)

The Ames Company had come a long way. A family blacksmith, cutlery and tool shop begun in Chelmsford, Massachusetts, sons Nathan P. Ames, Jr. and James T. Ames brought the business to a new manufacturing village on the Chicopee River in the Western Massachusetts town of Springfield in 1829 at the invitation of Edmund Dwight, whose family owned huge textile mill concerns, land and water rights on the river. The Dwights offered Ames four years rent free, and the Ames Company continued their tool and cutlery business, and also repaired the cotton textile machinery for Dwight’s mills. It was a short step from edged tools to edged weapons, and soon Ames began the manufacture of swords for the federal government and for state militias. (6)

Two mill villages settled along the Chicopee River in northern Springfield were called Factory Village and Cabotville. Cabotville was where Nathan and James Ames eventually chose to establish their firm in 1834. The swords were stamped variously “NP Ames, Cutler, Springfield” and “Ames Mfg Co., Cabotville,” as the firm evolved, and the year the weapon was made. (7) In 1848 this most northern section of Springfield split off and became a separate town called Chicopee, and their swords were now etched with this name, just as it was on the gold presentation sword made for Mexican War figure Brigadier General John A. Quitman, presented to him by President James Knox Polk, ordered on April 18, 1848, when the new town of “Chicopee” was a week old.

By the time Chicopee became a town the Ames brothers had become leaders of the community. They made and donated the school bell for the high school. When the Third Congregational Church was built a stone’s throw from their property in 1834-1836, Nathan donated $5,000 for its construction, half his personal fortune. (8)

That was also the year fellow townsman Alonzo Phillips invented the phosphorus match, representing only one of many industries coming to life in that town and many technological innovations that sprung from that still very small community.

The Ames Company itself began a host of new product innovations based on research and experimentation. Nathan was instrumental in the experimentation in new techniques and advances in gun making. By 1844, the company was producing the flintlock, breech-loading Jenks Carbine, for which Nathan was awarded the Silver Medal by the Franklin Institute. (9)

“The nature of my invention,” Ames wrote to Burton of another experiment, “consists in the…construction of a barrel of steel or iron of a uniform bore, and exterior taper, without welding…by modes of drilling and rolling the metal.” (10)

“I fell (sic) pretty certain,” wrote Chief of Ordnance Bureau Captain Henry A. Wise, who had visited the famed Krupps works of Germany, “that your method of putting iron and steel together in truth as good, if not the same as Krupp’s.” (11)

Nathan traveled extensively on business and made several trips to Europe. On one occasion in London, a dental procedure in which was used a paste of probably silver and mercury would in time poison him and leave Nathan in hideous pain, and slowly dying. He would eventually relinquish his leadership of the firm to his younger brother, James, as his health deteriorated.

By 1845, the railroad had come to Chicopee. The Republic of Texas was born, followed by the Mexican War, and by virtue of its government contracts for swords and side arms, Ames had a part in both events. It is interesting to note that the many of the members of the community, indeed in the state, did not support the war against Mexico. It would not the last time conscience clashed with business interests in the soon-to-be Town of Chicopee.

In the 1850s, several prominent farmers on Chicopee Street, which followed the Connecticut River northward from the village of Cabotville, were active players in secret rebellion against the Fugitive Slave Law as they allowed their homes to become stations on the Underground Railroad. These men were not the owners of the cotton mills which thrived on slave labor down South to produce their raw material, but presumably they were not more than a few pews away.

One local businessman whose conscience as regards slavery would later take a more violent turn was John Brown. He came to Springfield in 1846 to operate as a wool merchant and did business with Cabotville’s new Cabot Bank, established in May 1845. (12) John Brown owed $57,000 to the Cabot Bank from his miserably failing wool business. The Cabot Bank won a judgment against Brown. (13) John Brown left the area May 1849. (14)

While he was in Springfield, Brown received orator, author and former slave Frederick Douglass in his home. It may have been on the occasion when Douglass gave a lecture in Cabotville about his experiences, and it was with money from these touring lectures that he purchased his freedom.

Charles Dickens likewise spoke on another occasion, and “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” was performed in Cabot Hall. (15) The last Chicopee seems to have heard from John Brown was the letter written to Timothy W. Carter of the Massachusetts Arms Company in Chicopee Falls in February 1856 from Osawatomie, Kansas, requesting more carbines and ammunition to be shipped secretly. (16) James T. Ames, pillar of the Third Congregational Church, sold arms to both free-soilers and slavers. Conscience, conviction, and commerce wove a messy alliance.

Back at the Third Congregational Church of Cabotville was held the funeral of Nathan P. Ames in 1847. He was 43 years old when he died. According to The National Cyclopaedia, published in 1936 which contained scores of brief biographies of successful men of business and science, none of whom apparently were without gentlemanly virtues, Nathan and James were “men of exceptionally fine character and during their joint lives were deeply devoted to each other.” (17) Both were certainly men of great accomplishment, and with Nathan gone, the business, its enormous undertaking as well as its inherent commercial and philosophical consequences, was left on the shoulders of his younger brother, James Tyler Ames.

By 1849, the original capitalization sum for Ames of $30,000 had increased to $250,000. (18) A company of remarkable diversification, artwork was cast as early as 1835 when bronze statuary was created under Silas Mosman, who would cast the bronze doors of the east wing of the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. at the Ames Company, and would later include the “Minuteman” statue at the Lexington-Concord bridge, designed by Daniel Chester French, among his works. Along with works in brass and bronze, an iron foundry was added 1845, (19) and if the foundry was used for statuary, it was also meant for cannon.

By the Mexican War, the Ames Manufacturing Company’s main production had shifted to the making of arms, for the United States government and for foreign governments. The Chicopee Journal noted in September of 1854:

"The Ames Company of Chicopee have been engaged for

several months past in the manufacturing cannon, bombshells

and grape shot for His Most Serene Highness, Antonio Lopez

do Santa Ana. Of the last named article, two hundred tons

have been engaged, and we do not believe that the old, one-

legged humbug will have killed a hundred men after they are

all used up." (20)

Once again dictator of Mexico in between periods of exile, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna’s checkered relationship with his countrymen as well as with the United States did not prevent him from being a valued customer of the Ames Manufacturing Company.

It is interesting to note that though Ames had many contracts supplying weapons to state and town militias, besides the Federal Government, by the time of the political crisis of the Civil War that sent so many local civilian men into uniform, the fashion for town militia had faded in New England, certainly along with need for them. Chicopee’s Vital Records note that the Cabot Guards, their own town militia, received no appropriation of funds from the town in 1851, as they were about to disband. (21)

A few years earlier, the doomed Cabotville Chronicle took a break from lashing out at local industrialists to describe the military ball held at Cabot Hall in December, 1845 which “surpassed any thing of the kind we have ever seen in this village. The Hall was neatly and tastefully decorated…the music was the best that could be found this side of Boston or New York.” (22) The Hampden and Union Guards of Westfield also attended. Other than the community at last being seen free of Indian attack, it could also have been the distaste which many in town viewed the United States’ participation in the Mexican War which led to a mistrust and lack of enthusiasm for things with a military flare. Too, the old Yankee population with its colonial traditions was fading under new influences, like the Irish.

Most of Chicopee’s population of about 7,000, after its separation from Springfield in 1848, lived in Cabotville, and many of them were Irish immigrants huddled in the workers’ housing provided a stone’s throw from the mills by the factory owners.

"These factories employ 15,000 operators, many of whom are beautiful importations of the female sex from Erin’s Isle. The Ames Company employs 215 hands, and the Organization is second to none in Massachusetts." (23)

At the time of this 1857 Chicopee Journal article, the working day was 11 hours long, with a one-hour noon mealtime; in winter 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., and in summer 6:30 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. (24) The National Cyclopaedia reported of James, “As an employer, he was ahead of his time in enlightened treatment of his workers, with whom he was extremely popular.” (25) Whether or not this were true, the working conditions in his factory were certainly typical of the time.

James T. Ames lived in a brick house, also a stone’s throw away from his company. Ames’ mansion was built between 1844 and 1846. (26) It was a two-story brick house with a picket fence, built in the late Georgian style. Part of its treasures in later years when it became a museum were a bronze wall candelabra removed from the White House when gas lighting was installed, and an invitation to dinner from President Abraham Lincoln. (27)

Whether his trade was the by-product of an era or just capitalizing on it, Ames’ fortunes depended on political turbulence, and now there was plenty. With the coming political tensions in the year Abraham Lincoln would be elected President, the Federal Government passed legislation banning arms sales to states which threatened secession, but this would not go into effect until January 1861. Until then, Ames sold muskets and sabers to Southern militia, (28) but a shipment of gun making machinery sold to Virginia was diverted by Isaac Wright, Superintendent of the Springfield Armory early in 1861. (29)

When Virginia went with the Confederacy, so did James H. Burton, born in Virginia, who went to work at Harper’s Ferry Armory in 1846. In 1849, he had been promoted to Acting Master Armorer. Burton experimented with improved designs for Minié bullet. In 1854, he left Harpers Ferry and came to Chicopee to work with the Ames Company. A year later in 1855, accepted a five-year contract as Chief Engineer of the Royal Small Arms Manufactory in Enfield, England. In 1860, Burton contracted to be superintendent of the Richmond Armory, with machinery confiscated by the Confederacy from the Harpers Ferry Armory. (30)

Back in Chicopee, one of the last contacts of the days of town militia, Indian attacks and the fading Colonial veneer disappeared when Reuben Burt, soldier in the Revolutionary War, died August 8, 1860. Burt had also served in War of 1812, (31) another conflict like the Mexican War which had Whig versus Federalist coming to verbal blows and philosophical angst as to whether or not it was better or even right for Massachusetts to secede from the Union over it. Secession was apparently not so unthinkable then...

FOR THE SECOND HALF OF THIS ARTICLE, PHOTOS AND FOOTNOTES, PLEASE SEE MY BOOK:

Available in eBook and in paperback from Amazon and many other online merchants.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:33 AM

18

comments

![]()

Labels: 19th century, Civil War, manufacturing, Massachusetts