According to the “Byrne’s Dramatic Times” of Saturday, December 27, 1884, the theatre world in New England, and maybe in general, was hitting a rough patch. New Englanders had always been known among traveling players as being a region where people sat on their hands. On this date 123 years ago, it was lamented that the people weren’t even showing up.

“The Dramatic Times” was kind of like the “Variety” of its day. It gives us an interesting picture of what was happening on the boards, when the theatre world and its performers were considered exotic, and sometimes of questionable virtue. In New Haven, Broadway’s perennial anteroom, “Three Wives to One Husband,” which the Dramatic Times labeled an “extravagantly absurd comedy” played to “wretchedly small houses.”

Up in Bangor, Maine, “Prof. Mohr in legerdemain” played “to poor business” on the 12th and 13th. Over in Fall River, Mass., Callender’s New Minstrels played to a poor house.

Perhaps it was the material. In Boston, “Desiree” was performed at the Bijou, where “some extremely pretty and fascinating music is saddled to the worst rot imaginable, and the affect on the audience is to send them out in disgust or put them to sleep.” In the cast of this comic opera, we note of the popular 19th century actor and comedian DeWolf Hopper, “To Mr. De Wolf Hopper, the greatest praise is to be given, for in spite of his exaggerations, he is a true comic artist, and made all the success. Miss Rose Leighton, on the other hand, was the worst. What possible excuse she had for appearing is beyond me.”

Then again, maybe it was the critics who made theatre of the day so dismal.

Playwright, actor Dion Boucicault was in town with his “The Shaugraun” which would be followed by his “Colleen Bawn.” This is an interesting hint to us that the well-received Irish melodramas of this Neil Simon of the 19th Century indicates that in the twenty or so years since the Civil War, the Irish in New England had reached middle class status. Mr. Boucicault did a good business.

It is noted that after the performance of Boucicault’s play at the Museum, “Pique will follow.” One assumes this refers to the card game, and not the critic’s disdain.

Friday, December 28, 2007

Theatre in New England, December 1884

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:35 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: 19th century, entertainment, New England

Tuesday, December 25, 2007

I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day

This is the First Congregational Church of Chicopee, Massachusetts, built in 1825, though the congregation was organized in the previous century. The pastor of this church, Reverend Eli B. Clark, hid slaves on the Underground Railroad in secret rebellion against the Fugitive Slave Law in the 1850s. Several farmers in the neighborhood did the same.

In 1862, Reverend Clark helped to organize a rally in town to recruit soldiers for the Union Army. The early years of the war were bleak for the North, suffering defeat after defeat. That December, the Union forces were defeated again by the Confederate forces at the Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia.

It wasn’t until the Civil War years that Christmas began to be celebrated in some parts of Puritanical New England, prompted in part perhaps by the influence of hundreds of thousands of Irish immigrants in the previous couple of decades, and perhaps by the example of Great Britain’s Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, who championed the Christmas tree.

New England poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who had during the Civil War years lost his wife due to a tragic accident, and whose son was wounded on the battlefield, was moved both by his despair and by his hope for better days to pen “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day,” in 1864.

Later set to music, the song adapted from Longfellow’s poem as it is heard today does not usually contain all the verses which refer to the war. Here is the poem in its entirety.

Christmas Bells

I HEARD the bells on Christmas Day

Their old, familiar carols play,

And wild and sweet

The words repeat

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And thought how, as the day had come,

The belfries of all Christendom

Had rolled along

The unbroken song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Till ringing, singing on its way,

The world revolved from night to day,

A voice, a chime,

A chant sublime

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Then from each black, accursed mouth

The cannon thundered in the South,

And with the sound

The carols drowned

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

It was as if an earthquake rent

The hearth-stones of a continent,

And made forlorn

The households born

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And in despair I bowed my head;

"There is no peace on earth," I said;

"For hate is strong,

And mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!"

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

"God is not dead, nor doth He sleep;

The Wrong shall fail,

The Right prevail,

With peace on earth, good-will to men."

When news of the fall of Richmond reached Massachusetts in the spring of the following year, Reverend Clark rang his church bell at midday, and the sound carried for miles.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

8:32 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: 19th century, Civil War, houses of worship, literature, Massachusetts

Friday, December 21, 2007

Orchard House - Concord, Massachusetts

Louisa May Alcott was escorted in the gray December twilight to the train depot in Concord, Massachusetts by her sister May and their friend Julian, who was the son of their neighbor, author Nathaniel Hawthorne. It was 1862, and she was on her way to nurse Union soldiers.

The Civil War was a chance to test the idealism instilled by her parents and their Transcendentalist community, as well as a challenge to her own physical stamina and courage. Unexpectedly, it represented a turning point in her fledging writing career. Her identity as a writer, more than as a nurse, was forged during a traumatic taste of war in a Washington hospital.

One day in her classic novel Little Women, Alcott wrote of the war, “very few letters were written in those hard times that were not touching, especially those which fathers sent home.” Her own letters home to her family at this time formed the basis for a slim book called Hospital Sketches. With its detail of everyday events in the hospital, the book became a forerunner for her style used in Little Women, also set during the Civil War.

In “Little Women”, she drew the portraits of the four March sisters, their selfless mother and idealistic father from her own close family. The first part of that book was written in this house in Concord, called “Orchard House.” She had not grown up in the home; her family moved here when Louisa was already a young woman. It remains closely identified with the home of the fictional March sisters. It is an interesting contradiction that Alcott could not in the book which became her most important work, reveal the intensity of her war experience.

She arrived at her post time to help care for the mostly Union, though a few Confederate, wounded from the Union defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg. She tended wounds, assisted at amputations, comforted soldiers in agony during long hours on night duty.

Miss Alcott caught typhoid there, and was treated with calomel, a mercury compound whose side effects were debilitating. She left her nursing post in January 1863, a delirious invalid, as her father brought her home on the train. Her mother met her here at the Concord station. Unlike many other nurses and soldiers who contracted typhoid, Miss Alcott lived, though suffered from ill health the rest of her life and died at 55 years old.

This is the grave of Louisa May Alcott. The flag holder by the headstone is marked GAR, denoting her service to the Union in the Civil War, from which she could be considered a delayed casualty.

For more information on Orchard House, see this website.

Been there? Done that? Bought the T-shirt? Let us know.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

8:04 AM

4

comments

![]()

Labels: 19th century, Civil War, literature, Massachusetts

Tuesday, December 18, 2007

1101st CCC Camp, New Hampshire

This is the 1101st CCC, Thornton camp, West Campton, New Hampshire. These photos, from the CCC, were taken in the mid 1930s, part of a collage of several photos printed on a single 19½ x 12” sheet, as a souvenir for the young men and boys who were members of this unit.

Here are only a few of the boys and their commanding officers and kitchen staff. To quality for the Civilian Conservation Corps, what has been called the most popular of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, one had to prove neediness, such as a father who was unemployed. A hitch was six months long, and one could rejoin for as many as four hitches, for a total of two years.

These fellows worked on the dam in this photo. They built access roads. They worked in the White Mountain National Forest and made it a place we can enjoy today.

Sometimes they got to leave camp for church or to play baseball against a local town team. They earned $30 a month, most of which was sent home to their families. Some fellows were promoted to group leaders and earned a little more. Some finished their education in the C’s, and some didn’t like the military-style discipline and left. It was an experience none of them ever forgot.

For more information on the Civilian Conservation Corps, have a look at this website.

Been there? Done that? Served in the CCC’s or know somebody who did? Let us know.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:42 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: 20th Century, New Hampshire

Friday, December 14, 2007

Tobacco Shed

Imagine a typical New England farm and usually one might not place a tobacco shed there. Currier and Ives probably never thought so. However, it is as New England as that big red barn.

For thousands of years, native people gathered leaves from wild tobacco plants that grew along the banks of the Connecticut River in what would become Connecticut and Massachusetts. Today, tobacco farming is still an important industry. The shade tobacco variety typically grown here is used for the outer wrappers of cigars.

To a great extent, the story of tobacco agriculture is the story of America. The southern settlements in Virginia and the Carolinas in the colonial era were driven by tobacco production, which put the new European planters in conflict with the native people, and which relied on African slave labor.

Early New England colonists got the habit of smoking tobacco in pipes following the example of the native people, and began cultivating the plant. The Puritans, seeing evil in the plant, outlawed tobacco in Connecticut in 1650, but in the 19th century cigar smoking became popular, and tobacco farming became a major industry and a major employer. Many western New England teens of the 20th century and today may recall their first jobs in the tobacco fields.

There is less demand for the product now, and more demand by real estate developers for the land on which tobacco sheds like this one in western Massachusetts stand. But the industry, like most agriculture, continues at the mercy of the weather, the competition of foreign markets, and the whim of the consumer.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

8:17 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: 17th Century, 19th century, 20th Century, agriculture, New England

Tuesday, December 11, 2007

Quoddy Head and Passamaquoddy Bay

This is the Quoddy Head Lighthouse on Passamaquoddy Bay, Maine, whose 49-foot tower flashes light visible over 14 miles at sea, one hopes even on a foggy day like this. It was automated in 1988, and has been run on electricity since the late 19th century. The first wooden tower, built in 1808, was lit by sperm whale oil. This tower replaced it in 1857, with a lamp lit by kerosene in the 1880s.

Passamaquoddy, the name of the bay, comes from the native Passamaquoddy people. It is a Micmac word referring to the area of fertile pollock fishing.

During the War of 1812, the British occupied the area of what is now the Eastport, Maine. Just before and during this war, our boundary with Canada was not clearly defined, and establishing our presence with a lighthouse was part of making a claim as to where the border should be. The 1817 treaty established the lighthouse as being within the United States border, but the exact course of the boundary line in the area was still not settled until the early 20th century. West Quoddy, Maine is the easternmost point of land in the contiguous United states at 44° 49' N 66° 57' W.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:45 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: 19th century, lighthouses, Maine, War of 1812

Friday, December 7, 2007

Pearl Harbor Monument

Joseph Alfred Gosselin was an electrician’s mate on the USS Arizona at Pearl Harbor. On December 7, 1941, he was likely on duty in the radio communications center when the Japanese planes flew in, wave after wave, to attack the naval base.

Over one thousand sailors on the USS Arizona died that morning, and “Fred” Gosselin was one of them. He had already served nearly six years in the Navy, and was six weeks from being discharged. His family received official word, three months later that Fred was killed. They had held out hope until that moment. He was 27 years old.

This monument dedicated to the first man from Chicopee, Massachusetts to be killed in World War II, at the moment the war began for the United States, is located at the junction of Memorial Drive and Montgomery Street in Chicopee, now called Gosselin Square.

Remember Pearl Harbor? Let us know.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:40 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: 20th Century, Massachusetts, monuments, World War II

Tuesday, December 4, 2007

Ships and Subs of New London

This is the Eagle, a tall ship on active service with the US Coast Guard. She is harbored here in New London, Connecticut, and the juxtaposition with the Electric Boat Company in the background of this picture on the Thames River is as complimentary as it is ironic.

The tall ship had been launched in Germany in 1936 as Horst Wessel. Taken over by the United States, it was commissioned in 1946 into the Coast Guard. The Electric Boat Company’s history goes a bit farther back in the past, and a bit farther ahead into the future.

Financier Isaac Rice founded the Electric Boat Company in 1899, and in 1900 the US Submarine Force was established with the Holland, the world’s first practical submarine being built here.

Here is a magazine ad for Electric Boat during World War II. During World War I and just after, Electric Boat built 85 submarines for the U.S. Navy. During World War II, 74 subs and 398 PT boats were built here. In 1951 they began work on the Nautilus, the world’s first nuclear-powered submarine, completed in 1954.

New London, founded in 1646, was a navel base of operations as far back as the Revolutionary War. Today, it is home to the United States Coast Guard Academy, and home to the Eagle, and home to several nuclear-powered U.S. Navy submarines.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:44 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: 20th Century, Connecticut, manufacturing, World War II

Friday, November 30, 2007

Hammersmith Farm

Hammersmith Farm in Newport, Rhode Island, the childhood home of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, remains an impressive example of 19th century expression of wealth and social standing, when the lions of industry and society created havens for themselves, a place to get away from it all.

More subdued in style than the goliaths of architecture you’ll find on the Newport Mansions tour, the shingle-style 28-room cottage has the distinction of becoming an icon not of the Gilded Age but of the 1960s. The wedding reception of Jacqueline and John F. Kennedy was held here in 1953. Afterwards, during his presidency, the Victorian mansion was dubbed “the summer White House” by the press as President and Mrs. Kennedy were frequent summertime visitors.

With gardens originally designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, the lawns and meadows stretch to the bay. The dock there had once berthed the Presidential yacht “Honey Fitz.” However, Robert Redford also took advantage of it in the film “The Great Gatsby” (1974). Contrasting with this period of elegant notariety, the 50-acre property was still the last working farm in the city of Newport.

John W. Auchincloss, the great-grandfather of Jacqueline Kennedy's stepfather, Hugh D. Auchincloss, built the house in 1887. At the time this photo was taken, the mansion was open to the public for tours. Having been sold along with many of its original furnishings, the property is now privately owned, and it is now closed to the public.

The image of a young married couple being photographed in their wedding clothes against an expansive lawn bordered by a rustic rail fence is what most people who have not seen the property in person can recall. The former debutante and the former Senator made history, which was still part of the hazy future when their wedding photo was taken. Located on Ocean Drive in Newport, the mansion can still be seen from the road, and it has achieved the privacy which eluded it for so long.

******************

Jacqueline T. Lynch is the author of The Ames Manufacturing Company of Chicopee, Massachusetts - A Northern Factory Town's Perspective on the Civil War;

Comedy and Tragedy on the Mountain: 70 Years of Summer Theatre on Mt. Tom, Holyoke, Massachusetts;

States of Mind: New England; as well as books on classic films and several novels. Her Double V Mysteries series is set in New England in the early 1950s. TO JOIN HER READERS' GROUP - follow this link for a free book as a thank-you for joining.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:56 AM

7

comments

![]()

Labels: 19th century, 20th Century, movie locations, Presidents, Rhode Island

Tuesday, November 27, 2007

Last Look at Autumn

One last look at the glorious spectacle of a New England autumn, now already faded, before we bow to bare branches and snow-covered boughs. This photo was taken on the auto road up Mt. Greylock in Adams, Massachusetts.

My November Guest

By Robert Frost

My Sorrow, when she's here with me,

Thinks these dark days of autumn rain

Are beautiful as days can be;

She loves the bare, the withered tree;

She walks the sodden pasture lane.

Her pleasure will not let me stay.

She talks and I am fain to list:

She's glad the birds are gone away,

She's glad her simple worsted grady

Is silver now with clinging mist.

The desolate, deserted trees,

The faded earth, the heavy sky,

The beauties she so ryly sees,

She thinks I have no eye for these,

And vexes me for reason why.

Not yesterday I learned to know

The love of bare November days

Before the coming of the snow,

But it were vain to tell her so,

And they are better for her praise.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:35 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: literature, Massachusetts

Friday, November 23, 2007

Bellow Falls, Vermont - A Friendly Place to Hang Your Hat

This sign is painted on the side of building on Rockingham Street in downtown Bellows Falls, Vermont. Just across the street from the Miss Bellow Falls Diner, the building on which the sign is painted is owned by Frank Hawkins, who painted the sign and is noted locally for his work on other signs and murals, including a new one on the side of a barn up the road which attracts the motorist’s attention to “See Bellows Falls Vermont ….”

These signs sport a nostalgic look, but they are the product of a modern artist and a modern community which has found its own way of drawing attention from those who would bypass all of small-town America on the Interstate and never look back.

Look back. Better yet, turn back, and head into town instead of passing it by. Bellow Falls is not just a good place to hang your hat, it’s a good place to start your adventure.

Been there? Done that? Bought the T-shirt? Let us know.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:24 AM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: 21st Century, Vermont

Tuesday, November 20, 2007

Plimoth Plantation

The best thing about Plimoth Plantation is that none of the costumed interpreters ever breaks character. When you enter the stockade village, you enter the 17th century, with all its ills, its controversies, and its hope for a better future. You leave behind the 21st century, as much as you can, and the costumed interpreters will ignore any reference you make to television, automobiles, or Lindsay Lohan or Britney Spears.

Survival is what matters here, not the many affectations of a modern day affected society. The Pilgrims fought a life and death struggle for the first year of their presence in Massachusetts, which was made easier by the Wampanoag people who saved their lives by helping them to adapt. The Pilgrims and the Wampanoags were not exactly friends, but they were tenuous partners in a new experiment. Before the Pilgrims arrived, there were some 50,000 Wampanoag people in a territory around southern Massachusetts and eastern Rhode Island. The plague which killed thousands of them was probably brought to them by the Europeans settlers. Relations with the survivors dwindled until King Phillips War some decades later brought culture clash to devastating confrontation.

But the way of life echoed in the harvest celebrations that eventually became our Thanksgiving is an everyday occurrence here. The interpreters will not be dissuaded from intrusive questions on their eating habits and their funny clothes. They are righteous, self-righteous, and busy. Always very busy, though not too busy to share a bit of gossip with you about a neighbor as they pluck a chicken or wipe down a table, or repair a roof.

This is what makes Plimoth Plantation special, that the interpreters do not speak of the people of the era they represent in the third person. It is never “They did this,” or “They used this tool.” It is always, “I.” They portray people who existed, and they never let us forget that fact, because here in this special place they exist still.

Thanksgiving Day at Plimoth Plantation is an extraordinary experience, but the 17th century lies waiting for us here in Plymouth, Massachusetts the rest of the year as well. It is not to be missed. But leave your century at the door.

For more on Plimoth Plantation, visit this website.

Been there? Done that? Bought the T-shirt? Let us know. Happy Thanksgiving.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:47 AM

4

comments

![]()

Labels: 17th Century, holidays, Massachusetts

Friday, November 16, 2007

The Fort at No. 4

The Fort at No. 4 in Charlestown, New Hampshire is a re-creation of the fort which had stood in this area from 1740 to the 1760s. This was the northernmost English settlement along the Connecticut River in a time when New England could have become New France during the French and Indian War.

The settlers here were farming and trading families. They built a square of interconnected houses surrounded by a stockade, and crowned with a guard tower. Subject to a few Indian attacks, settler families abandoned the fort, replaced by militia troops in 1747, whereupon the fort was besieged again by French militia and Abenaki warriors. The seige lasted three days, but the English troops held out and the French and Indians withdrew to Canada. With the defeat of the French in 1761, and the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the need for the fort ended.

The fort illustrates for us today the commerce of the period, how important the river was for travel, and how the river opened up New England to settlers who found it difficult to travel otherwise through the dense forrests. Western New England is to a large extent demarcated from the eastern half by the settlement and commerce along the river. Our future industries, tourism, and even our accents derive from our north-south association, in an area of New England where Boston, the grand metropolis of American culture and history, has always seemed as distant as the moon.

Today there are costumed interpreters at The Fort at No. 4, and this replica of the 18th century should be included, along with Sturbridge Village’s 19th century and Plimoth Plantation’s 17th century replicas, as must see sights for New Englanders and travelers to New England, alike.

For more information on The Fort at No. 4, see this website.

Been there? Done that? Climbed the guard tower? Let us know.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:29 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: 18th Century, French and Indian War, New Hampshire

Tuesday, November 13, 2007

Mt. Holyoke World War II Memorial

Just a few minutes out of Westover Field in Chicopee, Massachusetts, a B-24 Liberator on a training mission slammed into the tree tops and rock cliff face of nearby Mt. Holyoke. It was May, 1944. The crew of ten on Army Air Corps flight training were killed instantly in the explosion.

In 1989 this granite monument was dedicated to their memory. Unlike many World War II memorials in the US, this monument does not merely commemorate these fallen men, it marks their place of death.

Most of the flight crew were not New Englanders. The radio operator was from Massachusetts. The wives of a couple of the crew members took apartments in South Hadley, and could have heard the crash that night, and the wail of sirens that followed. South Hadley fire fighters, as well as the fire departments of surrounding towns arrived to help put out the fireball on top of the mountain, and many civilians tried to claw their way up the mountain to reach the men, but it was too late for any rescue attempt. World War II was over for those men, and nothing would be the same for their families. It was a terrible accident that brought the war home to an otherwise quiet part of the world.

Been there? Tell us, or share your experiences at other New England war memorials.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:52 AM

5

comments

![]()

Labels: 20th Century, Massachusetts, monuments, mountains, World War II

Friday, November 9, 2007

Conway Covered Bridge

On Route 116 in Conway, Massachusetts, the Burkeville or Conway Covered Bridge stands, built around 1870 and is reported by one source as being the oldest surviving covered bridge in the US. Crossing the South River, it has the unique distinction of utilizing iron tension members into traditional timber truss work. These photos were taken more than a decade ago, though it appears to be autumn. There is something eternal about autumn.

The bridge has undergone restoration since these photos, and is now open only to foot traffic. There is some controversy in this country between restoring a covered bridge and rebuilding it to modern Department of Transportation requirements. Some interesting articles have been written on the subject. This bridge is on the National Register of Historic Places. Franklin County is home to about half of Massachusetts’ surviving covered bridges.

Been there? Done that? Spit off the bridge? Let us know.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:30 AM

4

comments

![]()

Labels: 19th century, covered bridges, Massachusetts

Tuesday, November 6, 2007

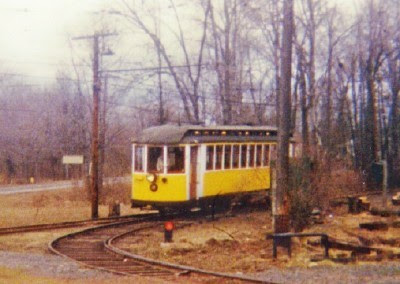

Connecticut Trolley Museum

The Connecticut Trolley Museum is the oldest museum dedicated to electric railroading in the US. The 17-acre site in East Windsor, Connecticut operates a mile and a half railway where visitors can take rides on running trolley cars. There are several trolleys and locomotives and railroad equipment among the museum’s displays.

You can ride the Rio de Janeiro Tramways car, the Montreal Tramways cars, or a streetcar from New Orleans, and try to imagine how this mode of transportation affected, and created, the realities of daily life so many decades ago.

From roughly 1890 to 1945, trolleys were a mainstay of public transportation not only within urban areas, but connecting cities. New England towns and cities were once connected with an extensive web of trolley lines. A lot were lost in the Hurricane of 1938, and many other routes were discontinued and tracks pried up during World War II.

For more info, visit the Connecticut Trolley Museum’s website.

Been there? Done that? Bought the T-shirt? Let us know.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:47 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: 19th century, 20th Century, Connecticut, Hurricane of 1938, museums, transportation

Friday, November 2, 2007

Red Sox World Series Souvenirs

From the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, here are a few mementos:

The program of the 1912 World Series, won by the Boston Red Sox.

The program of the 1915 World Series, won by the Boston Red sox.

A display of memorabilia from the 2004 World Series champions, the Boston Red Sox.

Time to make room for more World Series souvenirs.

For more information on the Boston Red Sox, have a look at this website.

Been to Fenway? Bought the T-shirt or the cap? Remember the Curse of the Bambino? Let us know.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:39 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: 20th Century, Massachusetts, New England, sports

Tuesday, October 30, 2007

Salem's Samantha Statue

Above is the statue of Elizabeth Montgomery as Samantha the nice suburban housewife witch of the 1960s television show, “Bewitched.” Located in Salem, Massachusetts, it is meant to reflect the tongue-in-cheek bemused attitude of the kitschy aspect of Salem’s present-day witch-inspired commerce.

There was a bit of controversy when the TV Land executives chose Salem, where many felt the idea was tactless. But in a town where the police wear a witch on a broomstick patch on their uniform sleeves, and the emblem is seen from the city hall to the high school, and Halloween-inspired souvenirs can be bought in stores here all year round, it is hard to complain about one statue devoted to a fictional witch.

Fictional being the operative word here, as we know Salem is most noted for the witch trials of 1692, which 19 men and women were hung, another was crushed to death, and others died in prisons. Samantha wasn’t a real person, and none of those murdered people were really witches. And Halloween to the modern American trick-or-treater is nothing like what the Samhein meant to the ancient Celts.

The historical sites and museums dedicated to telling the story of the infamous witch trials will be covered at another time. For now, it is Halloween, and that belongs to the present more than the past. Some of Salem’s history is tragic, some of it is triumphant. Some, like the statue of Samantha, is just silly and a bit cute.

For more on Salem as a tourist destination, visit this official website.

Been there? Done that? Bought the T-shirt? Let us know.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

8:00 AM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: 20th Century, holidays, Massachusetts

Friday, October 26, 2007

Halloween Candy - NECCO

With Halloween just around the corner, let’s have a look at one of New England’s premiere candy companies.

NECCO (New England Confectionery Company) has its roots as far back as 1847. It is the oldest multi-line candy company in the United States. NECCO’s current headquarters is located in Revere, Massachusetts. This company makes the classic NECCO® Wafers, Sweethearts® Conversation Hearts, Mary Jane®, Clark®, Mighty Malts®, Haviland® Thin Mints, and Candy House® Candy Buttons.

According to information found on the company website, Mr. Oliver R. Chase of Boston invented the first candy machine, a lozenge cutter in 1847. He and his brother founded the company which would become NECCO. In 1850, Mr. Chase invented a machine for pulverizing sugar. Eventually, confectioners Daniel Fobes, and William Wright, and Charles Bird would all enter what would become NECCO, which took the name New England Confectionary Company in 1901.

Their success has been far reaching. Reportedly in 1913, explorer Donald MacMillan took Necco Wafers on his Arctic expedition and introduced them to the children of the native people there. We don’t know if he introduced brushing and flossing to them as well. The following year the Charles N. Miller Company began producing Mary Janes, named for Miller’s aunt, and D. L. Clark began in 1917 to make candy bars named after himself. The 20th century was underway with a huge desire for candy.

Some of NECCO’s products are shown in the photograph above. If you buy them for the trick-or-treaters or buy them for yourself, you’re carrying on a long tradition of New England’s confectionary industry. Look at it that way. It might take some of guilt off.

Want to know more? Have a look at NECCO’s website.

Been there? Done that? Ate the whole bag yourself? Let us know.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:43 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: 19th century, 20th Century, holidays, manufacturing, Massachusetts

Tuesday, October 23, 2007

Lubec, the far east

Lubec is located, as the big sign says, at the easternmost point of the United States. Here’s where you go the beat everybody else in the US to the sunrise.

Situated on Maine’s Passamaquoddy Bay, the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Bridge connects Lubec to Campobello Island, in New Brunswick, Canada, a fascinating and very worthwhile place to visit, as much for us as it was for FDR. Lubec is a beautiful and rugged, and quiet place to be, a far different coastal experience than one might have in the more croweded and more commerical spots farther south in Maine. This is Maine as it used to be.

Settled in the 1780s, the town separated from Eastport, Maine in 1811, and was the site of a smuggling trade in gypsum after the War of 1812. There are four lighthouses in the area, and many opportunites for whale, seal, and puffin watches, cruises, and hiking. And a great sign to have your picture taken by.

Want to go? Have a look at this website.

Been there? Done that? Bought the T-shirt? Let us know.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:40 AM

4

comments

![]()

Labels: 18th Century, 19th century, Maine, War of 1812

Friday, October 19, 2007

Norman's Woe

Small and uninhabited and unlikely Norman’s Woe unaccountably looms large in New England maritime history, and also in literature. Often literature crosses paths, or crosses swords, with history. For Norman’s Woe, the story is of its many shipwrecks.

One shipwreck was of the “Rebecca Ann” in March, 1823 in a snowstorm. All ten crewmembers were swept out to sea, and one survived by holding on to a rock in the water. The Blizzard of 1839 wrecked many ships. Possibly the most famous shipwreck at Norman’s Woe was of the schooner “Favorite” out of Wiscasset, Maine, in December 1839. Twenty bodies washed ashore, among them that of an older woman tied to a piece of the ship. This was the event that poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow turned into his legend of “The Wreck of the Hesperus.”

Today Norman's Woe is a spot popular for deep sea diving, with great variety of marine life. It’s supposed to be a good place for lobstering. It is only a clump of granite jutting from the sea just offshore of Gloucester, and looks quite innocuous. But Longfellow has left us with a tragic story of sea captain’s foolish arrogance and his doomed daughter. It is foreboding and macabre.

There was a time when poetry was entertainment, and a poem with a regional flavor was like a guidebook, its descriptions substituting for photos, and ironically making us think we know the place better than a photo would. Below is the poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. If you never read it in high school, here’s your chance, go wild.

"WRECK OF THE HESPERUS"

It was the schooner Hesperus,

That sailed the wintery sea;

And the skipper had taken his little daughter,

To bear him company.

Blue were her eyes as the fairy flax,

Her cheeks like the dawn of day,

And her bosom white as the hawthorn buds,

That ope in the month of May.

The Skipper he stood beside the helm,

His pipe was in his mouth,

And he watched how the veering flaw did blow

The smoke now West, now South.

Then up and spake an old Sailor,

Had sailed the Spanish Main,

"I pray thee, put into yonder port,

for I fear a hurricane.

"Last night the moon had a golden ring,

And to-night no moon we see!"

The skipper, he blew whiff from his pipe,

And a scornful laugh laughed he.

Colder and louder blew the wind,

A gale from the Northeast,

The snow fell hissing in the brine,

And the billows frothed like yeast.

Down came the storm, and smote amain

The vessel in its strength;

She shuddered and paused, like a frighted steed,

Then leaped her cable's length.

"Come hither! come hither! my little daughter,

And do not tremble so;

For I can weather the roughest gale

That ever wind did blow."

He wrapped her warm in his seaman's coat

Against the stinging blast;

He cut a rope from a broken spar,

And bound her to the mast.

"O father! I hear the church bells ring,

Oh, say, what may it be?"

"Tis a fog-bell on a rock bound coast!" --

And he steered for the open sea.

"O father! I hear the sound of guns;

Oh, say, what may it be?"

Some ship in distress, that cannot live

In such an angry sea!"

"O father! I see a gleaming light.

Oh say, what may it be?"

But the father answered never a word,

A frozen corpse was he.

Lashed to the helm, all stiff and stark,

With his face turned to the skies,

The lantern gleamed through the gleaming snow

On his fixed and glassy eyes.

Then the maiden clasped her hands and prayed

That saved she might be;

And she thought of Christ, who stilled the wave,

On the Lake of Galilee.

And fast through the midnight dark and drear,

Through the whistling sleet and snow,

Like a sheeted ghost, the vessel swept

Tow'rds the reef of Norman's Woe.

And ever the fitful gusts between

A sound came from the land;

It was the sound of the trampling surf,

On the rocks and hard sea-sand.

The breakers were right beneath her bows,

She drifted a dreary wreck,

And a whooping billow swept the crew

Like icicles from her deck.

She struck where the white and fleecy waves

Looked soft as carded wool,

But the cruel rocks, they gored her side

Like the horns of an angry bull.

Her rattling shrouds, all sheathed in ice,

With the masts went by the board;

Like a vessel of glass, she stove and sank,

Ho! ho! the breakers roared!

At daybreak, on the bleak sea-beach,

A fisherman stood aghast,

To see the form of a maiden fair,

Lashed close to a drifting mast.

The salt sea was frozen on her breast,

The salt tears in her eyes;

And he saw her hair, like the brown sea-weed,

On the billows fall and rise.

Such was the wreck of the Hesperus,

In the midnight and the snow!

Christ save us all from a death like this,

On the reef of Norman's Woe!

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:44 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: 19th century, literature, Massachusetts, shipwrecks

Tuesday, October 16, 2007

The Breakers

The Breakers still stands as the stone and mortar embodiment of the Gilded Age. One of the Newport, Rhode Island mansions, a National Historic Landmark, the Breakers was built as the summer home of Cornelius Vanderbilt II, president of the New York Central Railroad. His most prominent family of industrialists led the social scene of the last years of America in the Victorian era. Vanderbilt’s 70-room summer home was built between 1893 and 1895, part of a 13-acre estate that faces east overlooking the Atlantic Ocean.

The interior boasts marble imported from Italy and Africa, alabaster, and wood and mosaics from various countries. The Great Hall is two and a half stories high. In the year it was completed The Breakers was the most opulent and largest house in Newport, once the social capital of America.

When Vanderbilt died in 1899, he left the property to his wife, Alice Gwynne Vanderbilt. She died in 1934 and the Breakers was left to her youngest daughter, Countess Gladys Széchenyi, who leased the property to the non-profit Preservation Society of Newport County. The Society bought the Breakers outright in 1972, though the agreement with the Society allows the family to continue to live on the third floor, not open to the public.

It is now the most-visited attraction in Rhode Island with approximately 300,000 visitors each year, open year-round for tours, one of several grand mansions open to the public in Newport.

Want to go? Contact The Preservation Society of Newport website.

Been there? Done that? Bought the T-shirt? Let us know.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:34 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: 19th century, Rhode Island

Friday, October 12, 2007

Mt. Washington

Mt. Washington was first climbed in the 1640s, but not much else happened here until the middle of the 19th century, when tourism was lured here with the construction of bridle paths and different summit hotels. The Tip Top House still stands, recently renovated. A stagecoach road was built, now called the Mount Washington Auto Road, and it is a breathtaking journey. It first opened in 1861, and is the oldest man-made tourist attraction in the US. If you receive the badge of honor, that bumper sticker that says “This Car Climbed Mount Washington” your car, its 2nd gear, and its brakes, have earned it.

For those less inclined to brave the winding vertical journey to the clouds, there is the less taxing Mount Washington Cog Railway, first constructed in 1869, which gives an enjoyable ride to the top. It is the oldest mountain climbing cog railway in the world. (It’s first proposal was ridiculed by the New Hamphsire State Legislature as a “railway to the moon.” Half-way to the moon, maybe.)

The top is something to behold, where the bald rock is exposed, the winds are fierce, and trees do not grow. On a clear day you can see Europe. Well, no, I’m kidding. On a clear day you can see the Atlantic Ocean, but clear days are not something one should count on. The mountain mist rolls in so suddenly, that if walking about the grounds around the summit observatory, it is best to stand still in your tracks until the cloud passes.

Snowstorms can occur at the summit in any month of the year. If you visit even in July, be prepared for a temperature drop of at least 30 degrees by the time you reach the top.

The summit building was designed to withstand 300 mph winds, and other buildings here are chained to the mountain. The mountain is the site of a non-profit scientific observatory reporting the weather and other elements of the sub-arctic climate.

Hiking is a favorite activity, but several avalances occur each year and many hikers have died for a variety of reasons. It is best to tackle the mountain only if you are prepared for its unique challenges. Above the tree line, it is a different and treacherous world, but a place of stunning beauty.

Auto races and bicycle races also take place up the mountain. However you choose to get to the top, take a good, long, look. It’s worth the effort.

Want to go? Have a look at this website. Also check out information on the Auto Road and on the Cog Railway .

Been there? Done that? Bought the T-Shirt? Let us know.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

8:35 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: 19th century, 20th Century, mountains, New Hampshire

Tuesday, October 9, 2007

Mt. Holyoke Summit House

It is a small mountain, only just over 900 feet, but overlooking the broad terrain of the Pioneer Valley, the perspective is panoramic. This month the Summit House will close for another year.

A summit house was first built in the 1820s, and went through various owners and renovations to become by the 1850s, quite the stop for well-to-do tourists. An early visitor in 1823 was Ralph Waldo Emerson. A tram was built up the mountain to bring visitors, along with stage coaches up the winding road. Eventually the Summit House boasted upper levels, extensions, elegant dining rooms, and such architectural embellishment that even President William McKinley could not resist its charms, and visited in June of 1898, whereupon he headed down the mountain to attend the graduation of his niece from Mount Holyoke College.

The Hurricane of 1938 tore up a chunk of the building, (Was there nothing that mammoth storm did not touch?) and the Summit House entered its declining years. Deteriorating over the next several decades, supporters kept the building from being demolished and a restoration project in the 1970s and early 1980s gave the Summit House back to Western Massachusetts. From its cozy height, you can see the patchwork farms and the winding Connecticut River, and other companionable mountain ranges that makes the view from the Summit House veranda one of the most easily accessible of lofty inspirations.

Want to go? Now part of the Joseph A. Skinner State Park, have a look at this website for more info.

Been there? Done that? Bought the T-Shirt? Let us know.

Posted by

Jacqueline T. Lynch

at

7:35 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Hurricane of 1938, Massachusetts, mountains